Entertainment

SYOWIA KYAMBI TALKS ABOUT HOW ART SAVED HER LIFE

Syowia Kyambi a multimedia, interdisciplinary artist and curator spoke to Buzz Central about her latest exhibition dubbed Kaspale. She also opens up about the challenges of being an artist in Kenya and how art saved her life.

Give us a short background about yourself.

I was born and raised in Nairobi, and I’ve been making art since I was a young child. When I was young, my art teacher was Theresa Musoke, a fabulous Ugandan artist. In my teenage years, I was with Liza Mackay, Morris Foit and Patrick Mukabi. I have powerful memories of that time in my life. I also have strong memories of being 15 and Richard Kimathi coming and working with Theresa Musoke in my parents’ back garden. I think these are the people who formulated, influenced and supported my art and my parents. For my higher education, I went to Art Institute of Chicago for my BFA and received my MFA from the Transart Institute.

What inspired you to become an artist?

Art was a lifesaver for me. The art process really helped me so much, art was an anchor, I needed an outlet to process all the things happening around me.

Why did you decide to team with Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI) for your latest work KASPALE?

KASPALE, the exhibition at the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI), is the only one that has featured elements of every part of the Kaspale project. However, it’s still only showing a quarter of what the Kaspale project because of unique and curatorial decisions. Previously, I presented one work connected to KASPALE in the MARKK Museum in 2019, but that is a specific work titled, Kaspale’s Archive Intrusion. There was never an idea of doing a project. It just became a work of art that I kept exploring, and what you have at NCAI is a presentation of that exploration.

The last time you showcased in Nairobi was seven years ago; why was this the right time for you to come back?

I exhibited a single work in a group exhibition in 2018. There is generally a long gap between solo shows as it takes time to develop work for solo exhibitions. I think the other factor that contributed to this is that my work tends to be a large scale 7 – 14 meters, and we don’t have those kinds of spaces yet; the Nairobi National Museum is one. But a lot of the other spaces are not really big enough.

Many focus on short exhibitions, usually from two weeks to a month. I think that’s unfair, given the amount of financing that goes into working on a show and the amount of effort for the artists and the people working in the space/institutions. It’s really intensive labour for very many people. Then to show it for two weeks, I think, it’s not enough. We should be cultivating and providing space and time for longer exhibition schedules.

While performing as Kaspale, you use a mask; what is the inspiration for the mask?

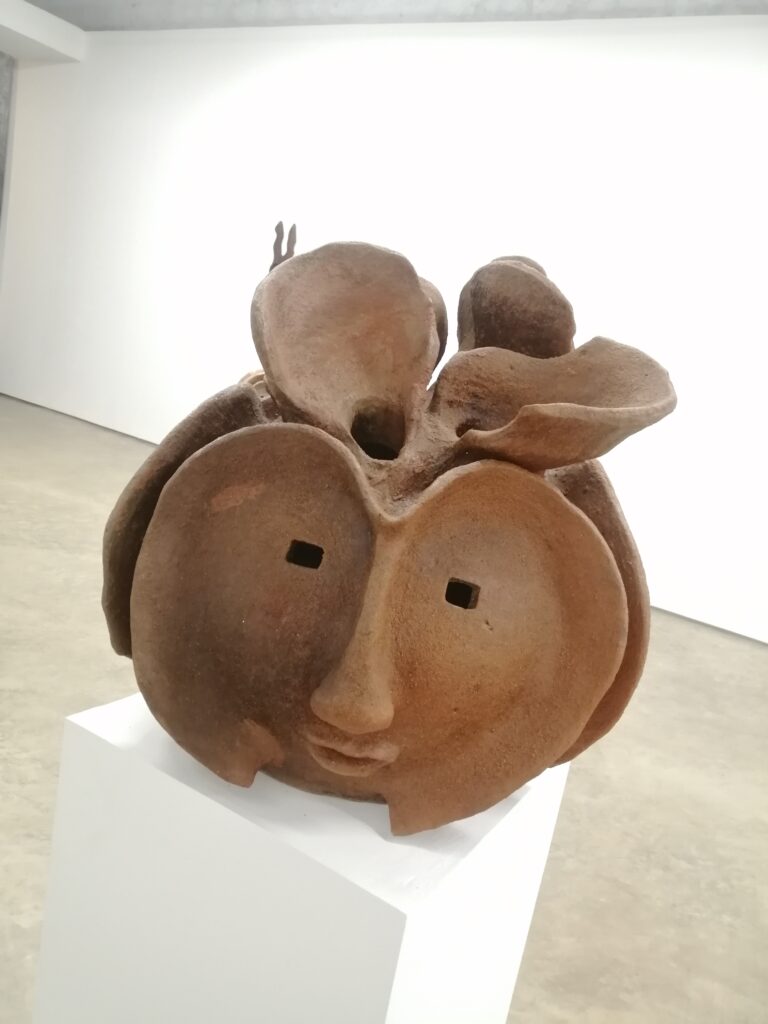

The mask is a double face. There’s Kaspale with the golden lips, and Kaspale with the face mask. They can see, hear and speak in multiply. The mask was inspired by a Makonde mask, which is situated in the MARKK Museum, Hamburg, in their archive. In 2019, I was there, and I was interested in Makonde making because of an idea I had around imaginary spaces and connecting to the imaginary. So the mask kind of landed on my lap, and I was very attracted to it. The Makonde mask inspired the design for the first mask I created, which can be seen in the work titled, Kaspale in the Lecture Room (2019), an unfired stoneware ceramic mask. That was the first mask I made for the character, Kaspale.

On your latest show, you decided to dig deep into Kaspale’s character; why was it important?

It’s a body of work I’ve been working on for the last four years. When NCAI approached me to do an exhibition with them, it was the obvious choice for the scale of the exhibition space they offer, as other works of mine would require a more expansive space, and we would, therefore, only be able to showcase two to three works. So, presenting a small part of the Kaspale body of work was a logical option. I created the character, Kaspale, to have a tool I could use as an intervention for themes that are hard to communicate and topics that are difficult to digest, hear about and speak about.

In your latest exhibition what mediums do you use?

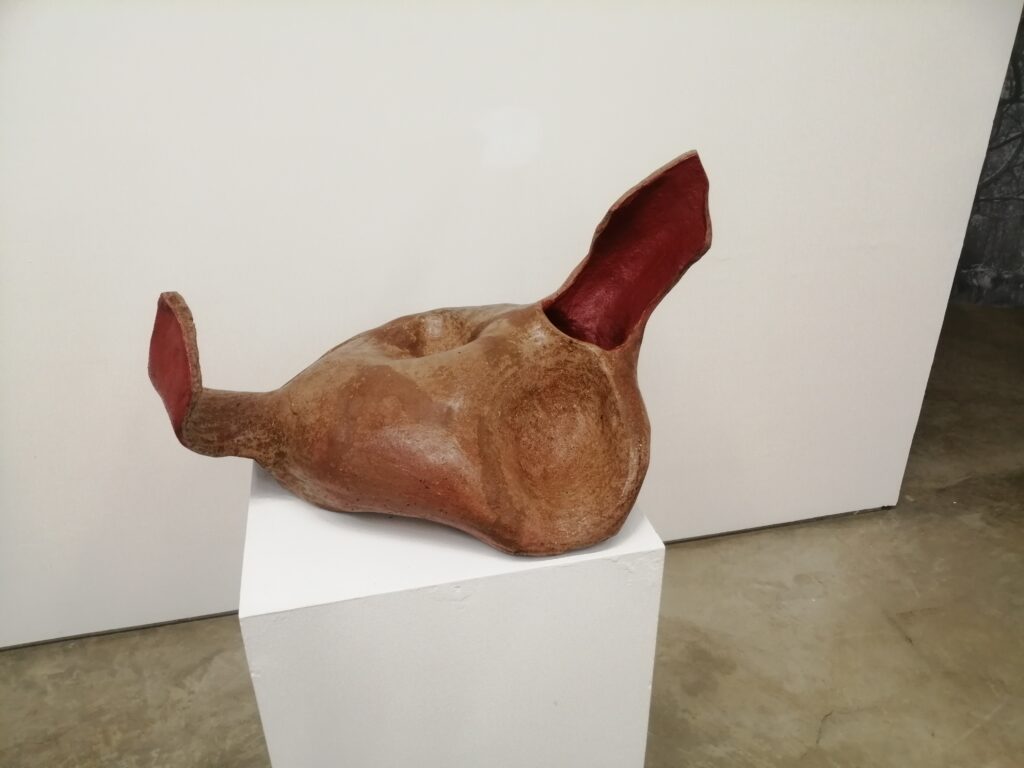

I use various mediums for the sculptural work, from ceramics to recycled dhow wood to aluminium. It’s an exploration of materiality. I love working with ceramics as it is a medium that is unpredictable and organic and has a process that includes a softness in the making and a solid, strong form once it is fired.

What are some of the challenges you are facing as an artist?

We need to have better support structures for the development and exposure of ephemeral work and celebrate work that is not only geared towards a commercial art market. We need better legal systems to safeguard artists so they don’t get harassed by police when working in public spaces, for example, if we are photographing in the street. We need a better support system where we don’t get censored inside national spaces. Finally, we need to create an understanding in society that art can be more than a hobby; it is also serious work, a profession.

You are the co-founder and curatorial creator of Untethered Magic; tell us more about it.

Untethered Magic is a home first and foremost, and it’s a space where we host residencies and develop time for artists away from production. We’re not interested in production but in process and exchange. We’re also definitely focused on being autonomous and self-sustainable. We have built some small accommodation structures that we run on a local tourism market to cycle funding back into the arts.

We also have a mentorship program in collaboration with NCAI, which kick starts later this year and offers higher education for artists. However, this is not yet formally accredited. That’s a long-term project to build upon and further develop the educational platform for artists to access higher education, with mentors from all over the world who understand the context we are working within and who operate in the international art industry.

Who are your biggest artistic influences?

When I was young, it was, obviously, Theresa Musoke. Then, as I got older in my late teens, it was Frida Kahlo and Ana Mendieta, particularly Ana Mendieta. Then Louise Bourgeois is an artist whose practice I find myself very drawn; it is fascinating and layered. Now I am part of a collective called What the hELL she Doin! The artists in that collective are also significant artistic influences for me and offer a support system of more: Sonia E Barrett, Usha Seejarim and Immy Mali.

What would you say is the purpose of your work?

My work aims to bring to the forefront what is not in the history books so that we can create more profound dialogues about how the past has affected the present and the potentialities of our futures. There are many omissions that take place in the stories of our lives, and I’m just unearthing that which has been erased or forgotten or that we need reminding of.

Are you open to collaborating with other artists?

I’m in constant collaboration with other people. I don’t believe that you make art in isolation. For me, even conversation is a form of collaboration. I work with people for film editing in many different parts of the world, depending on where I work and our proximity to each other. I also write and have some people who always feed back their writing to me. I surround myself with people who also are not working in isolation.

What memorable responses have you had to your work?

In 2011, I performed a work titled Fracture (i), an installation and a performance that lasted about two and a half hours. It was a museum space, so there were no chairs, and viewers could come in and leave at will. And two grandmothers stood there the whole time, watched the entire performance, and cried at the end. They could relate to the work, which was about Kenya. The work’s aesthetics and references were not their references. They were Finnish women. I don’t know from which part of Finland, but they connected with the work. At that moment, in 2011, I became more aware that there’s something very human in the themes I explore, and that’s why people could connect, regardless of where they come from. That was an extraordinary moment.

Advice to upcoming artists

Be prompt in responding to your administrative tasks. If somebody writes to you and wants to see something or a portfolio, don’t take your time to send it because there are many people who are just as good as you, if not better. When you get a no on an application for something, don’t worry too much about it; keep writing applications. I can make 15 applications and get one acceptance, so don’t give up. Also, remember that relationships are key. Build long-term relationships and engagements with people from both the same and different disciplines from yours. Finally, be honest with yourself and those around you.

0 comments